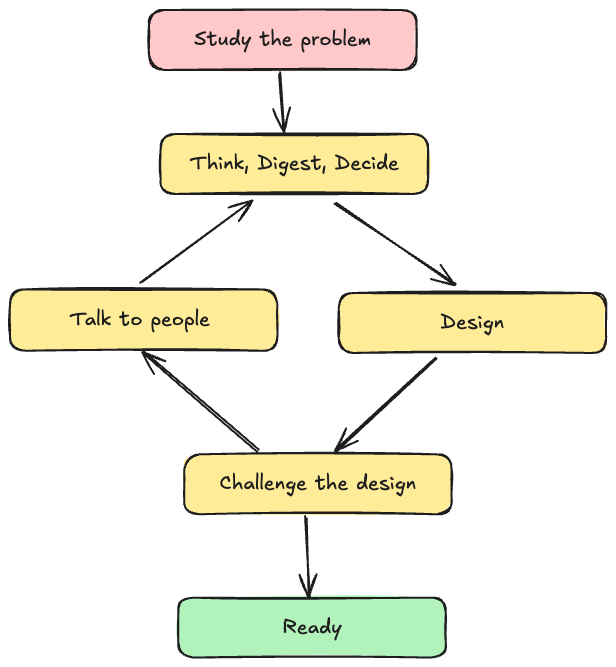

The Design Loop: My Notes on How Initial System Designs Evolve

The process of design is similar to me to the process of writing. I can’t confirm or deny that I’m good at it. To be honest, I’m not sure if there is a definitive way to align on a certain definition of “good” in that context.

But I know the process that makes me able to draft a better version than the previous one. and that’s what I’m here to discuss.

The Process: Everything starts from a problem

1. Study the Problem

The beginning is usually simple: a big problem everyone is staring at. From the outside, it looks clear from the outside. It can range from fixing a brownfield project to creating a new greenfield one. What’s missing for most people is the detail. What are we actually facing?

Your first step: do your homework and study the problem.

Studying the problem goes beyond reading whatever document exists. You need to draft the details yourself and create a starting point—a shared definition of what the problem is, how it started, and what caused it. Understand the past and present to set the stage for the future.

Sometimes the details feel shallow and scattered. Don’t worry; that’s common. Your best tool here is documentation. The one you write after gathering every relevant piece of information.

2. Think, Digest, and Decide

Once you’ve collected enough information to organize your thoughts, start the thinking process. Put everything in front of you and start connecting the dots.

What helps me is printing the key documents and studying, marking, and taking notes with pen and paper. This might differ in your case. The important step is to connect the dots.

Imagine Dr. House sketching on the whiteboard, brainstorming with his team about possible diseases based on the symptoms.

3. Start drafting an initial design

Draft an initial design that captures your initial thoughts. It probably won’t be the final one, but it’s crucial to move forward.

This initial draft becomes the basis for all next steps; it’s the one that you will iterate on. It may be abstract and light on details. Don’t worry about that. The most important thing is to draft this design in a format that you can edit and adjust. There are plenty of tools out there that you can use, for example draw.io . Pick what suits you and your company’s style. The tool matters less than its ease of iteration.

4. Challenge the design

Before moving on, challenge the design using what you know about the problem. Does it work for basic cases? What about edge cases? When does it fail? Does it address everything you currently know, or did something drift?

If you find something that you missed, try adding it to the draft. If you find yourself stuck or can’t see what’s missing, it’s time for the next step.

5. Talk to people

You have challenged your own design with the information you had; now it’s time to talk to people and make them challenge it and give you different views. and maybe additional context that can help you evolve this design.

This step is tricky. Who do you talk to? How do you give them context?

What works for me is 1:1 conversations with people who have more experience or a different perspective—often stakeholders or adjacent teams. People from outside usually provide great insights and ask sharp questions that can help reveal blind spots.

Why 1:1s? They create focus and usually end with clear action items. They’re more controllable and productive than larger meetings. Don’t get me wrong, the wide audience meetings are useful but mostly for later stages. From my observations, once you exceed 3–4 people in a meeting, it gets harder to steer and often end without clear outcomes.

I prefer the wide range one in the latter stages of the design, when things become more solid, and I need alignment with the wider team on the final touches.

6. Take the feedback and repeat

After challenging your draft and talking to people, collect the feedback and update the design to the next version.

As you repeat this loop, watch and observe how your understanding of the problem and your solution evolve. That evolution is one of my favorite parts: witnessing your steps toward the solution.

This process may seem simple, but it requires effort and the right mindset. The key here is Don’t get attached to your design, and don’t take anything personally.

The goal is to build the right feedback loop and iterate until you reach alignment with the objective, the problem, the primary and edge use cases, and the stakeholders.

7. It’s time

Here you start the journey of implementation. At this stage, If you iterated enough, changes should be minimal. There are cases when you will find changes needed during implementation. Document them and ask yourself, what did you miss? Why did this appear now and not earlier?

This will make you evolve as well. It’s your feedback loop driven by actual experiences in the battlefield.

Good design isn’t a one-shot thing; it’s a loop. Study, draft, challenge, talk, iterate, ship—then learn and repeat.